Nature is not something

out there, apart from people.

It never was, and nowadays people have built and farmed and clearcut

so much that wildlife species from insects to birds are in trouble.

In south Georgia people may think that our trees make a lot of wildlife habitat.

Actually, most of those trees are planted pine plantations with

very limited undergrowth, and in town many yards are deserts of grass

plus exotic species that don’t support native birds.

Douglas Tallamy offers one solution:

turn yards into wildlife habitat by growing native species.

Since we are as always remodeling nature, we might as well do it

so as to feed the rest of nature and ourselves,

and by the way get flood prevention and possibly cleaner water as well,

oh, and fewer pesticides to poison ourselves.

Nature is not something

out there, apart from people.

It never was, and nowadays people have built and farmed and clearcut

so much that wildlife species from insects to birds are in trouble.

In south Georgia people may think that our trees make a lot of wildlife habitat.

Actually, most of those trees are planted pine plantations with

very limited undergrowth, and in town many yards are deserts of grass

plus exotic species that don’t support native birds.

Douglas Tallamy offers one solution:

turn yards into wildlife habitat by growing native species.

Since we are as always remodeling nature, we might as well do it

so as to feed the rest of nature and ourselves,

and by the way get flood prevention and possibly cleaner water as well,

oh, and fewer pesticides to poison ourselves.

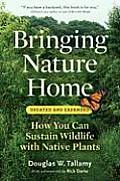

Douglas Tallamy makes a clear and compelling case in

Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants

Bringing Nature Home: How You Can Sustain Wildlife with Native Plants

…it is not yet too late to save most of the plants and animals that sustain the ecosystems on which we ourselves depend. Second, restoring native plants to most human-dominated landscapes is relatively easy to do.

Some of you may wonder why native species are so important? Don’t we have more deer than we can shoot? Maybe so, but we have far fewer birds of almost every species than we did decades and only a few years ago.

Some may wonder: aren’t exotic species just as good as native ones,

if deer and birds can eat them?

Actually, no, because many exotic species are poisonous

to native wildlife, and because invasive exotics crowd out natives

and reduce species diversity.

From kudzu to

Japanese climbing fern, exotic invasives are bad for wildlife

and may also promote erosion and flooding by strangling native vegetation.

to native wildlife, and because invasive exotics crowd out natives

and reduce species diversity.

From kudzu to

Japanese climbing fern, exotic invasives are bad for wildlife

and may also promote erosion and flooding by strangling native vegetation.

All plants are not created equal, particularly in their ability to support wildlife. Most of our native plant-eaters are not able to eat alien plants, and we are replacing native plants with alien species at an alarming rate, especially in the suburban gardens on which our wildlife increasingly depends. My central message is that unless we restore native plants to our suburban ecosystems, the future of biodiversity in the United States is dim.

Tallamy had an epiphany when he and his wife moved to 10 acres in Pennsylvania in 2000:

Early on in my assault on the aliens in our yard, I noticed a rather striking pattern. The alien plants that were taking over the land —

the multiflora roses, the autumn olives, the oriental bittersweets, the Japanese honeysuckles, the Bradford pears, the Norway maples, and the mile-a-minute weeds — all had very little or no leaf damage from insects, while the red maples, black and pin oaks, black cherries, black gums, black walnuts, and black willows had obviously supplied many insects with food. This was alarming because it suggested a consequence of the alien invasion occuring all over North America that neither I — nor anyone else, I discovered, after checking the scientific literature — had considered. If our native insect fauna cannot, or will not, use alien plants for food, then insect populations in areas with many alien plants will be smaller than insect populations in areas with all natives.

Insects are the key, because most birds eat insects, thus indirectly feeding even birds that eat other birds. And insects mostly specialize on specific plants. Why? Because many plants produce chemical compounds that are toxic to insects that aren’t specialized on them, or that just plain taste bad.

Exotic plants, on the other hand, are often chosen because few native insects will eat them. Even if they aren’t chosen for that reason, there usually aren’t many native insects that will.

How many fewer?

One of the surprising parts of the book (to me, at least)

was that much of the research to answer that question didn’t exist,

and Tallamy and colleagues had to go out and do much of it,

while collecting the few studies of specific insects or specific

plants that had already been done.

They chose butterfly and moth larvae as the insects to study,

because so many birds eat those.

was that much of the research to answer that question didn’t exist,

and Tallamy and colleagues had to go out and do much of it,

while collecting the few studies of specific insects or specific

plants that had already been done.

They chose butterfly and moth larvae as the insects to study,

because so many birds eat those.

The answer is: a native plant typically feeds 10 to 100 times as many native butterfly or moth larvae as an exotic plant. The humble goldenrod, for example, is a favorite of many insects.

But don’t they adapt? Yes, but very slowly. He provides a table that illustrates just how slowly:

| Plant Species | Herbivores Supported in Homeland | Herbivores Supported in North America | Years Since Introduction to North America | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clmatis vitalba | 40 species | 1 species | 100 | Mcfarlane & van den Ende 1995 |

| Eucalyptus stellulata | 48 species | 1 species | 100 | Morrow & La Marche 1978 |

| Melaleuca qunquenervia | 409 species | 8 species | 120 | Costello et al. 1995 |

| Opuntia ficus-indica | 16 species | 0 species | 250 | Annecke & Moran 1978 |

| Phragmites australis | 170 species | 5 species | 300+ | Tewksbury et al. 2002 |

That’s right, a hundred years or more and still only a few native herbivores will eat these plants. Insect evolution to consume new foods takes longer than that, possibly thousands of years.

Tallamy points out that exotic doesn’t necessarily mean imported across an ocean, either. Species from the western U.S. can be exotic in the eastern U.S., for example.

Tallamy says right off that his is not a how-to book, but in addition to lists and pictures of exotic invasive plants to avoid, he does include some rough lists of likely native plants for your yard, organized by large geographic areas.

Unfortunately, being from Delaware, he’s a bit vague about

the U.S. southeast.

For example, among trees he doesn’t even mention longleaf pines.

Fortunately, there is a book for that,

Native Trees of the Southeast: An Identification Guide

by L. Katherine Kirkman, Timber Press (OR).

Once you have some native trees, consider

Forest Plants of the Southeast and Their Wildlife Uses

by James H. Miller, University of Georgia Press.

Unfortunately, being from Delaware, he’s a bit vague about

the U.S. southeast.

For example, among trees he doesn’t even mention longleaf pines.

Fortunately, there is a book for that,

Native Trees of the Southeast: An Identification Guide

by L. Katherine Kirkman, Timber Press (OR).

Once you have some native trees, consider

Forest Plants of the Southeast and Their Wildlife Uses

by James H. Miller, University of Georgia Press.

The beauty of Tallamy’s book is it makes the case for native plants for native insects for native birds and other diversity that will help wildlife and also help humans directly. I already gave this book to several people for presents. I recommend everyone with a yard buy this book. You don’t need ten acres; you don’t even need a quarter acre: you can do this right where you live.

-jsq

Short Link: