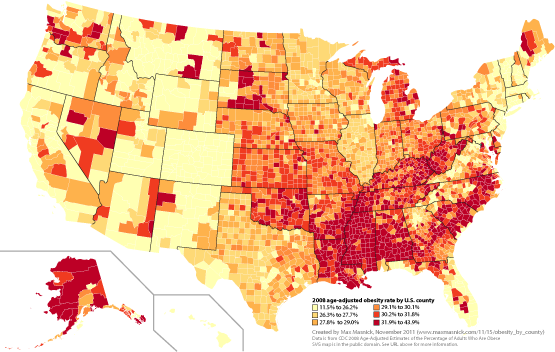

This is why there is an epidemic of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease in the U.S.: food deliberately engineered to make people eat until they get fat. Georgia is not quite one of the fattest states, but Lowndes County is one of the fattest counties. There is something we can do, even while Big Food continues to act like Big Tobacco.

Michael Moss wrote for NYTimes 20 February 2013, The Extraordinary Science of Addictive Junk Food,

On the evening of April 8, 1999, a long line of Town Cars and taxis pulled up to the Minneapolis headquarters of Pillsbury and discharged 11 men who controlled America’s largest food companies. Nestlé was in attendance, as were Kraft and Nabisco, General Mills and Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola and Mars. Rivals any other day, the C.E.O.’s and company presidents had come together for a rare, private meeting. On the agenda was one item: the emerging obesity epidemic and how to deal with it. While the atmosphere was cordial, the men assembled were hardly friends. Their stature was defined by their skill in fighting one another for what they called “stomach share” — the amount of digestive space that any one company’s brand can grab from the competition.

James Behnke, a 55-year-old executive at Pillsbury, greeted the men as they arrived. He was anxious but also hopeful about the plan that he and a few other food-company executives had devised to engage the C.E.O.’s on America’s growing weight problem. “We were very concerned, and rightfully so, that obesity was becoming a major issue,” Behnke recalled. “People were starting to talk about sugar taxes, and there was a lot of pressure on food companies.” Getting the company chiefs in the same room to talk about anything, much less a sensitive issue like this, was a tricky business, so Behnke and his fellow organizers had scripted the meeting carefully, honing the message to its barest essentials. “C.E.O.’s in the food industry are typically not technical guys, and they’re uncomfortable going to meetings where technical people talk in technical terms about technical things,” Behnke said. “They don’t want to be embarrassed. They don’t want to make commitments. They want to maintain their aloofness and autonomy.”

A chemist by training with a doctoral degree in food science, Behnke became Pillsbury’s chief technical officer in 1979 and was instrumental in creating a long line of hit products, including microwaveable popcorn. He deeply admired Pillsbury but in recent years had grown troubled by pictures of obese children suffering from diabetes and the earliest signs of hypertension and heart disease. In the months leading up to the C.E.O. meeting, he was engaged in conversation with a group of food-science experts who were painting an increasingly grim picture of the public’s ability to cope with the industry’s formulations — from the body’s fragile controls on overeating to the hidden power of some processed foods to make people feel hungrier still. It was time, he and a handful of others felt, to warn the C.E.O.’s that their companies may have gone too far in creating and marketing products that posed the greatest health concerns.

The combination of salt, sugar (esp. the carefully engineered mix of sucrose and fructose on HFCS), and fat in fast foods has produced an epidemic of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. This combination is pushed by the soft drink and fast food companies, and high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in most other processed foods adds to the damage, pushed by their vendors. The whole mess is propped up with corn subsidies and laws that let Monsanto get away with letting its seeds drift and then prosecute neighboring farmers for seed theft, whille deliberately-planted MON seeds require massive amounts of pesticides, detected in the urine of school children from Kansas to Manhattan. Then there are the CAFOs with their chickens that can hardly stand up and cattle that are never allowed outside, both pumped full of antibiotics from birth or hatching to slaughter, breeding antibiotic-resistant bacteria and with traces of the antibiotics left in the “food”. In other words, it’s actually worse than this article says. But what it says is bad enough.

Mudd then did the unthinkable. He drew a connection to the last thing in the world the C.E.O.’s wanted linked to their products: cigarettes. First came a quote from a Yale University professor of psychology and public health, Kelly Brownell, who was an especially vocal proponent of the view that the processed-food industry should be seen as a public health menace: “As a culture, we’ve become upset by the tobacco companies advertising to children, but we sit idly by while the food companies do the very same thing. And we could make a claim that the toll taken on the public health by a poor diet rivals that taken by tobacco.”

This was in 1999. The CEOs in the room acted predictably. Like tobacco executives before them, they refused to change.

Roger Rosenblatt wrote for NYTimes 20 March 1994, How Do Tobacco Executives Live With Themselves?

PEOPLE WHO WONDER how tobacco company executives can live with themselves conclude that they must be in denial. That would explain how they deal with their responsibility for a product that kills more than 420,000 Americans a year — surpassing the combined deaths from homicide, suicide, AIDS, automobile accidents, alcohol and drug abuse. But to be in denial implies that one may not be held accountable, in psychological terms, for one’s actions. Tobacco people squarely face the accusation of accountability, and reject it.

The picture is of seven tobacco companies’ heads swearing before Congress that their products were not dangerous, even though they all knew the evidence that tobacco kills.

L.A. Times 15 April 1994, 7 cigarette makers deny adding nicotine,

“We have looked at the data . . . [and] it does not convince me that smoking causes death,” said Andrew H. Tisch, chairman and chief executive officer of the Lorillard Tobacco Co.

Back to the 2013 NYTimes food article:

…the one C.E.O. whose recent exploits in the grocery store had awed the rest of the industry stood up to speak. His name was Stephen Sanger, and he was also the person — as head of General Mills — who had the most to lose when it came to dealing with obesity….

…Sanger began by reminding the group that consumers were “fickle.” (Sanger declined to be interviewed.) Sometimes they worried about sugar, other times fat. General Mills, he said, acted responsibly to both the public and shareholders by offering products to satisfy dieters and other concerned shoppers, from low sugar to added whole grains. But most often, he said, people bought what they liked, and they liked what tasted good. “Don’t talk to me about nutrition,” he reportedly said, taking on the voice of the typical consumer. “Talk to me about taste, and if this stuff tastes better, don’t run around trying to sell stuff that doesn’t taste good.”

To react to the critics, Sanger said, would jeopardize the sanctity of the recipes that had made his products so successful. General Mills would not pull back. He would push his people onward, and he urged his peers to do the same. Sanger’s response effectively ended the meeting.

Sanger is retired as GM CEO now, but he’s

a director of Target Corporation (since 2001) and Wells Fargo & Company (since 2003), and formerly served on the boards of Dayton Hudson, Donaldson, Grocery Manufacturers of America, and Minnesota Business Partnership. Sanger is a board member of Catalyst, the Guthrie Theatre, and the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, and a member of the Business Council and the US Advisory Committee for Trade Policy and Negotiations.

Forbes lauds his “seasoned, broad business perspective”. Food company executives, unlike tobacco executives, continue to ride high, while the obesity and disease problem continues to get worse.

Georgia isn’t quite one of the worst states for obesity. But Lowndes County is one of the worst counties, in the 31.9% to 43.9% obesity range, and that was for 2008:

Mapping U.S. obesity rates at the county level

by Max Masnick 15 November 2011.

This is one reason why

South Georgia Growing Local & Sustainable Conference

will be in Lowndes County in January 2014.

Other reasons include promoting the economy of south Georgia,

and good food tastes better.

See you there.

This is one reason why

South Georgia Growing Local & Sustainable Conference

will be in Lowndes County in January 2014.

Other reasons include promoting the economy of south Georgia,

and good food tastes better.

See you there.

-jsq

PS: NYTimes junk food engineering article owed to Barry Shein.

Short Link: