Much current discussion of the ACES climate bill that passed the House

is about whether it will really cost one postage stamp per person per day,

or maybe two stamps.

This is like arguing what microcomputers will be used for in 1980.

I fondly recall a prediction that

“We’ll never sell millions of them unless there’s one in every doorknob!”

Well, look at your average hotel today: there’s one in every doorknob.

David Roberts posts on grist.org about

Why we overestimate the costs of climate change legislation,

12:09 AM on 29 Jun 2009:

David Roberts posts on grist.org about

Why we overestimate the costs of climate change legislation,

12:09 AM on 29 Jun 2009:

As for modeling innovation, that’s always been the Achilles heel of economic forecasting. In this piece, Eban Goodstein and Hart Hodges trace a history of cost overestimations around environmental regulation. Again and again, models have underestimated the pace of business and technological innovation.

Today’s modelers surely do all they can to incorporate innovation. (As Brad notes, the CBO tries.) But there are constraints to how precisely this can be done. In 1980, McKinsey reported to AT&T that mobile subscriptions would rise to 0.9 million by 2000. The real number turned out to be … 109 million. (This factoid is among many interesting tidbits in

this presentation from Vinod Khosla.)

Vinod Khosla was one of the founders of Sun Microsystems,

the company that mainstreamed computer workstations,

has long been a venture capitalist,

and has been investing successfully in renewable energy for years.

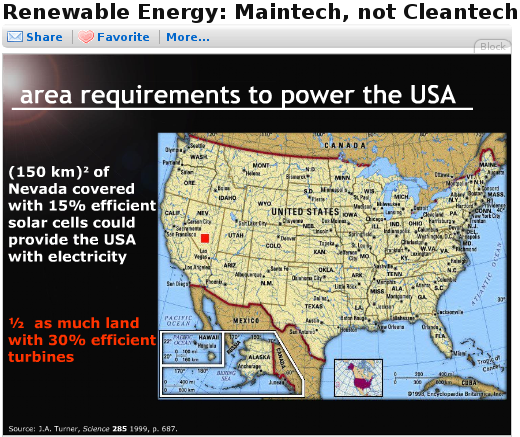

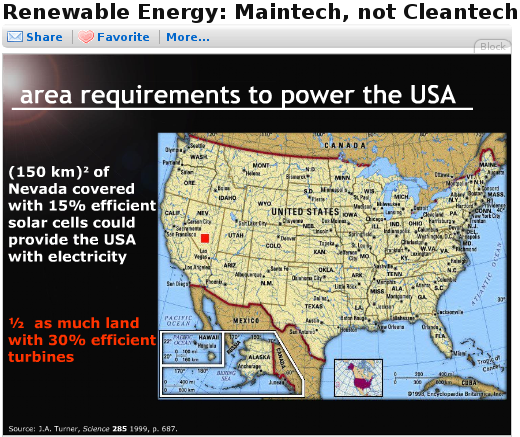

The little red square in the Nevada desert is all the area it would

take to

power the U.S. with solar panels.

And that’s before further efficiency improvements.

No reason it all has to be in Nevada, of course:

Georgia has a lot of sun.

Distributed is better than centralized.

In memory of that old privateer, Commodore Essex Hopkins (1718 – 1802),

first ranking officer of the U.S. Navy, and my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, here’s a picture of the Commodore’s flag: DONT TREAD ON ME.

In memory of that old privateer, Commodore Essex Hopkins (1718 – 1802),

first ranking officer of the U.S. Navy, and my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, here’s a picture of the Commodore’s flag: DONT TREAD ON ME.

In memory of that old privateer, Commodore Essex Hopkins (1718 – 1802),

first ranking officer of the U.S. Navy, and my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, here’s a picture of the Commodore’s flag: DONT TREAD ON ME.

In memory of that old privateer, Commodore Essex Hopkins (1718 – 1802),

first ranking officer of the U.S. Navy, and my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, here’s a picture of the Commodore’s flag: DONT TREAD ON ME.